"When I think about using the term [brown], I think about a sense of belonging which I think is particularly important in spaces where you many times don’t feel like you belong at all." | Brown, Reimagined: Book Launch of Brown is Redacted

Recording of Brown Is Redacted Book Launch

The book launch of Brown Is Redacted took place at the Screening Room at The Arts House on 20 November 2022, Sunday. You can watch the recording above and access the full transcript of the programme on this page. Portions of the transcript have been edited for clarity.

About Brown Is Redacted:

This programme is co-presented by Singapore Writers Festival and Ethos Books. Singapore Writers Festival is organised by the Arts House Limited and commissioned by the National Arts Council.

--

You can find the speaker bios at the bottom of this page. Enjoy the conversation!

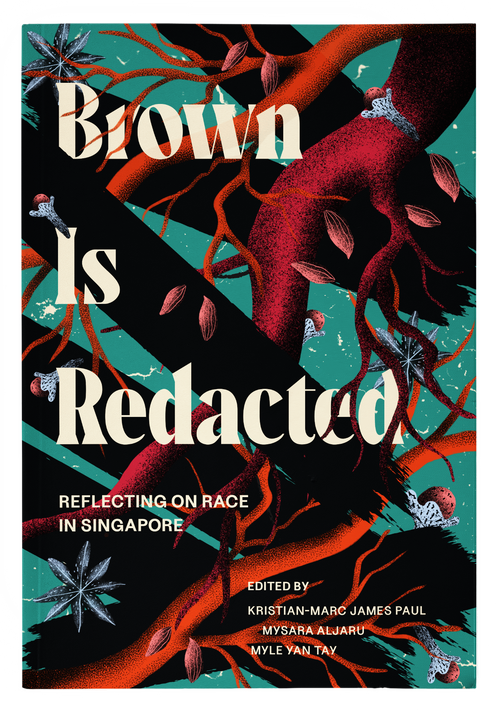

Photo of the panelists. Left to right: Kristian-Marc James Paul, Laika Jumabhoy, Mysara Aljaru, Paul M. Jerusalem (moderator) and joined by Myle Yan Tay (Zoom).

🌳

Arin: Hi everyone! Thank you for joining us at The Arts House. I’m Arin from Ethos Books and a warm welcome to the launch of Brown is Redacted: Reflecting on Race in Singapore.

Paul: Thanks so much Arin for the lovely introductions of all five of us. For this session, all of us are talking as friends, as people who have a lot in common and have many different specificities to our experiences.

And brownness as a label, as a category. Different people have said different things about the concept of brownness, but we gather here today united by this overarching concept of brownness as something that has been useful in our writing, in our work, in helping us to understand not just ourselves but also the people around us, in our communities, and people that we interact with.

I'm not going to go too deep into that, to give everyone time for their thoughts, but this is something that we’ll return to later.

For today’s talk, we really want to focus on Brown is Redacted as a standalone text, which does contain the script [for Brown is Haram], but also many other different texts that have been contributed by other people.

The first question is for Kristian, Mysara or Yan. Some of us here have watched the play Brown is Haram, and Nabilah’s essay in the book tells us more about the name which is a riff playing on the phrase “Dadah itu haram”, which refers to the tagline behind an anti-drug campaign targeting the Malay community to tell them drugs are haram.

It’s quite interesting that, instead of retaining the same name as the performance lecture, you have decided to go with “Brown is Redacted”. Tell us more about your thought process behind this.

Kristian: I’ll start off by giving two points as to why we decided to change the name. First of all, Brown is Haram, the performance lecture, was something very special between me, Mysara, then eventually Yan also, and we wanted to maintain the sanctity of the performance lecture which was very, very special; it was a very particular moment of us sharing our vulnerabilities and stories with each other.

The second reason is that we also wanted to show that this was just an evolution of the performance lecture. It was more than just our voices. The performance lecture was really just our three stories, and we wanted to convey that with Brown is Redacted, it’s really not our stories, it’s an anthology of different voices and the aim of the anthology was to expand the narratives, to expand the stories that could be told.

The second thing I would say is, when we had decided that we were gonna change the title, we kept asking ourselves: what were we trying to say about brownness and what was the anthology trying to say about brownness?

The thing we kept coming back to is, which we articulated in the introduction, is that there is a sense of intangibility. You can’t really touch it, you can’t really hold on to it, but beyond that, also a sense of hiddenness, right? That sort of “true brownness”, or “authentic brownness” is oftentimes hidden or curtailed in Singapore, where the trope of the model minority is so overwhelming. That’s why we went with something like “redacted”, to convey that hiddenness.

Paul: Thanks for that, Kris. Yan and Mysara, any additions to that? There are two overarching points. First of all, maintaining the sanctity of the performance lecture. We call the book a standalone text, and to name it the same thing would be to suggest that it is merely that, but you’ve talked about how it is an expansion from just a performance lecture, and renaming it is important to signal that the two are connected but separate things.

And second of all, what we’re trying to say about brownness. You talk about the intangibility of brownness, how difficult it is to pin down, as well as the concept that for some people there exists a “true brownness”. What do we even consider “true brownness”? This is something that the performance lecture captures, as well as the other works in the collection.

When you say ‘redacted’, what comes up at the top of my mind as someone who’s terminally online is that ‘redacted’ is like a meme among social media circles, particularly on Twitter, when people want to have plausible deniability, and they want to say something about something else that might be construed as critical, they would replace the entity that they’re talking about and say, “blah blah blah, -redacted-, blah blah blah.”

There’s a cheekiness to it, a playfulness to it that is often used in a very ironic way. That irony is captured in the performance lecture. So with regard to ‘redacted’, why ‘Brown is Redacted’ and not simply ‘Brown is Erased’ or ‘Brown Has Ceased to Exist’?

Mysara: I think there’s a lot of reasons for it. Partly because when you use the word ‘redacted’, there’s this implication that certain narratives are forced to be erased, which is what we are trying to implement and highlight. There are certain tropes or narratives about minority people that we see often in mainstream media, and other narratives are hidden, right?

When you talk about minorities, the first thing that you would think about would be Malay or Indian. What about our migrant workers, or Filipinos, or Indonesians, we often forget about them. They’re just not there. But we don’t think about them because these narratives are not often brought out by state media, for example. You have to be actively talking to people in the community to understand what they’re going through. So that’s one reason.

Also, this idea, going back to the model minority, how we view minority is what essentially an extension of what we understand as the Singapore identity. To be a minority you need to be either very successful, right, like what I wrote about in my part of the play. You have to get a NUS law degree or whatever, or you go to the other extreme, where you live in a one-room flat, you have five kids at the age of 23 or something like that.

It’s either extreme, which is not actually like lived realities. I was telling Paul, whenever I write, I think of minahs on Twitter and what they say: “You know my name but not my story.” They have a point! They look like a stereotype; you don’t bother asking them about what it’s like to live their lives.

We make assumptions, we make stereotypes. Minahs have a point on Twitter; you know their name but you don’t know their stories.

Paul: I love that point you raised about how, because of the myth of the model minority, minority-race people are expected to either be exceptional or a cautionary tale to warn the rest of the community. It’s a very reductive tale, and what you say about this notion of 'true brownness' and the 'perfect model minority', leads me to something that really captivated me in Laika's work.

It opens with this poetic sequence where it talks about something along the lines of “don’t go into the sun, you’re brown enough,” and something that struck me was usually the word ‘enough’ is used to affirm people, saying, “I am enough, I don’t have to meet certain standards.” But in this poetic sequence there was almost a “you are brown enough, so don’t go and enjoy yourself in the sun.”

Something I really loved was how your work touched on intergenerational racial connections and relationships. The person you talked about being brown enough was someone from the older generation who has a very close connection to you. In particular, your work troubles one tempting narrative of racism as being something that solely comes from the oppressor, fleshing out the way that it is sometimes or often enforced by the very ones who raised us.

Sometimes it’s subconscious, but in your work, you really trouble this narrative, and show how even something that’s supposed to be affirmative is sometimes used to draw the boundary between being acceptably brown and too brown. What were your hopes with this piece, “Beauty In Me”?

Laika: I think you’ve pointed out some of the hopes already in that I particularly chose words that should in theory be very easy to interpret and, like you said, 'enough' is almost always seen as affirmative, but in using this kind of language I wanted to bring out the confusion that a lot of us feel when we are growing up in terms of what is acceptable and what is not.

And really to highlight that it isn’t always in-your-face comments, or things that are really obvious to you, but is done through grandparents saying things, and parents going like, “okay, so what?”, and then it perpetuates over the generations and leaves you in this confused space. I wanted to bring out that tension. Because on some occasions you’re told to tie your hair really tight, go to school, don’t let too many curls out.

Then on others like Diwali they’re like, “come on, show your curly hair, wear all those bangles, speak properly.” So in using that kind of language is to really bring out the everyday confusion that you don’t realise until much, much later as well.

Paul: That’s beautiful, thank you for that Laika. For those who are here just to see whether you want to end up spending money on the book, if this doesn’t tempt you, I don’t know what will. It ends off with this very beautiful excerpt that I want to read out, because it returns to the notion of being enough and turns it into something beautiful again, and reclaims the term from something that was used intergenerationally as a source of hurt and pain. So here I read:

(This is talking about the speaker’s daughter): “My heart warms as she proudly proclaims, “I am fiery jam tart warrior princess!” I am caught off-guard at the self-assured assertion. “I am beautiful. Don’t want clips or hair tie,” silencing any attempts to tame her curls. As she grows, I pray this fire does too, anchoring her from retreating into herself as she faces question after question.

Gazing at her tiny fingers clasped around one of my crutches as we head out to play, I hope that she sees that there is beauty in her and me.

I am afraid, yet I am sure, we will be enough.”

We were talking about intergenerational racial politics and trauma here. Something very powerful that you do is you show how you break that cycle. And it’s not something that is easy, but comes from the natural perception or natural beauty that stems from the younger generation that hasn’t yet been exposed to as much of the external forces that try to quell our brownness, so I really love that. Thank you.

Laika: Thank you.

Paul: Back to Yan, Kris and Mysara. In terms of curating a collection of writing, all of you had a very close hand in inviting people to be a part of this and putting out a call for submissions. The process of curating this is very different from writing a performance lecture, I’m sure.

What were some lessons that you learnt during the process of writing or curating this, and how did this differ from the process of writing Brown is Haram?

Yan: On curating/working with the performance, I found that editing the work was very similar to directing the production in terms of the internal motivation; the principles that we were operating on. In both senses, for the book and the play, what I was trying to do as editor or director is to make sure that the people who are generously sharing these stories are getting the spotlight. And that there’re as few barriers between the person reading or watching and the story they’re hearing. They’re just sharing that moment together.

With the production, what we were trying to do was to make a comfortable physical space that felt honest, vulnerable and real, and one of the goals of the book was to try and recreate that sensation, but in a more abstract way. Again, executing that took a different set of tools than what we would do on the stage.

One of the biggest things for that, with the book, was the sequence. We spent a lot of time debating what the order of the texts should be, what should come first, what should come after which. You can pick up the book and you can just open up any chapter and read it and you’ll be fine and you’ll enjoy what you’re reading, but we also wanted to try and create this throughline, this narrative that people could follow, feel the mood shift with people’s words.

Part of that was also thinking about how to section the book, because the book is split into four different sections, which was very difficult because these experiences aren’t really neatly sectioned. So that was operating more on instinct.

Paul: Thank you Yan. You mentioned how directing the play was actually not too dissimilar from curating the book. How about for Kris and Mysara; you really poured forth all the very real and visceral experiences that you have from your entire life history, and some of them I really related to very much. In working with people beyond yourselves, were there any interesting lessons or different things about the experience?

Kristian: For me, the question that I kept asking myself was negotiating between editing a work and not gatekeeping or curtailing someone’s art and how they express art, especially for something that is so visceral, so material, that is tied very much to what they’ve experienced.

How do you acknowledge and honour that while still having your editor hat on and thinking about where it goes in the book. Can this be heightened or amplified in a certain way to bring out a specific sentiment or emotion? So that for me was something that I took away; this delicate balance that is still something that I think about. The negotiation between amplifying someone’s art and the more technical, slightly more utilitarian things that go into the act and process of editing.

Paul: It's alright that you don't have all the answers right now, because these thoughts will form as people read the book, come up to you, and tell you about how it evoked certain emotions or sentiments in them. Similar to after the performance lecture, I remember standing outside and just pouring forth everything I felt about it to you. So later there will be a chance for that to happen as well, for those who’ve read it.

That brings us to our last question. A common charge by people who are not big fans of the conceptual term 'brownness'—assuming that they oppose the concept for reasons other than racism or a resistance to progressive or anti-racist politics—is that the term flattens the multifaceted experiences that non-Chinese and non-White people in this part of the world have. In other words, the term groups the experiences of Malays with those of Indians, as well as those of the middle class minority races with those of the working class or, even more glaringly, those whose existence in this country is predicated by their enforced marginal status in the form of a Work Permit. For those who are unaware, a Work Permit dictates you’re here in Singapore for a duration of time; there’s no pathway to citizenship under the Work Permit.

Even if you were to somehow fall in love with someone who’s a local, you need to get your employer’s permission in order to be able to marry that person. And this is something that I learnt in one of the essays here by HOME, so excellent choice there. But bringing us back to the question, how have you decided to embrace 'brown' as a concept in spite of these charges that have been brought forward?

Mysara: In the introduction, Kris and I have acknowledged the limitations of the term 'brown'. It’s this idea of shared experiences, like when you go to work for example, and maybe there’s only one Malay one Indian person and your colleague starts speaking in Chinese and you exchange that look with your brown colleague?

You know that look, right, that expression. It’s those moments where you have that little bit of solidarity that we also wanted to bring about. When we did the play, we recognised that both of us have very different experiences. Laika and I have very different experiences. How do we talk about it and acknowledge it at the same time?

For me at least, 'brown' is a term of acknowledgement that even though we have different class backgrounds, there is something we share, living as minorities in this country. That’s how I see it.

Paul: So brownness as something that unites these shared experiences. How about Kris, Laika, Yan?

Laika: Quite similar to Mysara - many terms have problems with them, and you can go and pick out all the problems, but when I think about using the term, I think about a sense of belonging which is particularly important in spaces where many times, you don’t feel like you belong at all.

So being able to use a common term, and even, as [Mysara] said, to have those glances and bits of commonalities even though there might be many differences, is very, very important.

Similarly, using a common term allows you to highlight whichever differences you want to. Your brownness is different from mine, and it’s okay, and it can be highlighted in different ways. I think that’s the uniqueness of using a common term in that way.

Paul: And the term is not just common but straightforward. No one will hear the word 'brown' and go, “huh? What does brown mean?” It’s obvious that you’re talking about a particular group of people, even if the exact definition of what that group is is a bit more open to interpretation. Yan, any thoughts on the use of ‘brownness’ as a conceptual term or category?

Yan: For me, the question is, what is the point in categorisation and what does that do? Brown as a category to me is about as helpful as CMIO (Chinese, Malay, Indian, ‘Other’). It subsumes, it ends up swallowing up people’s individual experiences, and that’s part of the project with this book; to take out the individual story and make that the centrepiece rather than the collective categorisation that you can slap onto any person.

Paul: So use the term not as a limiting category, but something that opens up, not just conversations, but other ways of thinking.

Mysara: If I can add on, one critique that people would say is "it’s a concept that you take from the West". My personal response would be, you’re not listening to us, you’re not understanding what we’re trying to say, you’re focusing on terms.

At some point all of us would be online and would see this whole debate about whether we should use the term ‘Chinese privilege’ but no one is discussing the issue behind it, or the experiences or structural issues. It’s a form of distraction, essentially.

Sure, we can talk about it and we should talk about it, about whether we form a new term or stick to this term, but generally if your focus is on "oh you guys are taking this from the West", but not engaging in the discourse, then I think it’s a distraction rather than an attempt to tackle the issue.

Paul: Exactly, that’s a great point. The term ‘brownness’, while our endeavour is to open up other ways of thinking, being able to be vigilant against attempts to reduce it to a scapegoat, to distract people from the issue at hand. This awareness and vigilance against such actors is very important as well.

I see this book as a kind of textbook that we never had, and even the metaphor for textbook isn’t great, because a textbook is something that we memorise in school, but I mean textbook in a way that for many of us brown people who never really had a collection of stories by people like us growing up, this helps to open up our eyes to things that we’ve gone through but never really had the language to talk about.

It’s not just academic essays. It centres, also, people’s very real lived experiences, and that’s something I really love about it.

There’s three questions by Megan (on Slido). Let’s go with the most highly-voted question first.

Race and any accompanying tensions have always been sensitive topics in Singapore—did the team face any issues with censorship? If no, can say no, it’s okay.

Mysara: In terms of, “no, you cannot write this,” no we have never experienced that.

Paul: So in other words this very ambitious project has been accompanied by an editorial team as well as a publication that is very supportive of narratives that might not be in line with the OB markers, so-called.

Next question. Wai Kit asks, "Some feel that ‘brown’ is a reductive term because it incorporates tropes of colourism that are foreign to Singapore discourses about ‘race’.” In addition to what Wai Kit asks, I also want to bring up about CMIO being as useful as brownness in terms of how reductive and limiting it can be. So what do all of you feel about ‘brown’ being seen as a reductive term?"

Kristian: Something that we try and say in the book also is that this anthology is merely one thing and there are many, many stories that we could not incorporate or did not incorporate. And I remember the three of us, having conversations about colourism and that also being a form of privilege also, right? How can you navigate the world if you look a certain way as opposed to another way?

How then can you survive this world because your skin is of a lighter colour? That’s definitely something that we talked about.

Mysara: Honestly I don't think it’s that foreign. Maybe our parents, our grandparents didn't use the word ‘brown’, but I think they would talk about the same things we experience in some sense. Maybe it’s foreign because we have social media now and everyone’s speaking about it publicly, but I think it’s very important to note that these calls and conversations about race are not new and foreign.

It might seem new and foreign to you because you’ve never had to face it. You’ve never had that discussion with your parents. You've never had your dad coming back home and go, “yeah, I’m the only Malay man in the office”. It may seem foreign because at that time there was no Twitter. I don’t know where this discourse will go next, but yeah.

Paul: Something that just came to mind about CMIO being compared to brownness is, is CMIO itself not a Western import? It stems from this categorisation of race from the colonial administration that somehow we retained and have no problem embracing despite its roots?

It’s not necessarily an unproductive question to ask about whether you’re blindly adopting something that came from Western cultural discourse, but in asking that question, also pay attention to other discourses that were imported. So what if something was imported or influenced by thinking in another part of the world? If it’s useful, we make it our own, not blindly adopt it wholesale. If it’s not useful then obviously we wouldn’t adopt it.

There’s this question from Arun: Hazirah Mohamad's racialised health framing piece's critique of reductive explanations of unequal health outcomes amongst minorities challenges the dominant state narratives as well as addresses how this has been internalised by minorities. What do you think would be a next step in addressing this?

In addition to what Arun asks about the next step in addressing this, how do you also see this book as having a role in looking at this narrative from the state as well as other racialised, dominant ideas about race?

Yan, we’re all looking at you.

Yan: Yeah it’s a big question. The way I view the book is it’s meant—even though there are a lot of great academic pieces in there—it’s in a way anti-statistics, it’s not meant to be an encyclopedia, it’s meant to be a catalogue of people’s experiences. And some of those fall under these state narratives or defy them, but I think it’s more about looking at people, which is not the inclination of a governing body.

Paul: Right, so this book being anti-statistics and letting the stories not only speak for themselves but also trouble the notion that everything that is statistical is what should be seen as the unchallenged truth. These individual stories, even if they are not experienced by 70% of people, still matter.

Returning to Arun’s question; the reason why I edited the question is Hazirah is not on this panel, so I don’t know if anyone would be able to answer this, but the question Arun asked was what do you think would be a next step in addressing these dominant state narratives that have been internalised by minorities?

Mysara: I think a nice first step would be—even within your friends and family—especially if you’re Malay, you open Berita Harian, the first thing you see is diabetes. Recently they roped in the Indian community as well. Not everyone has access to data and statistics, so we tend to take it wholesale.

Now that you’ve read what Hazirah wrote, you have a more critical understanding of how the state uses numbers, data, bring it up to your friends and your family. Say hey, this is not everything, whatever this report has is not a complete understanding of issues in our community. Issues of health, for example, often ties to issues of class and access to healthcare. That is often not brought in (on purpose, I would say) when we talk about health in brown communities, in minority communities. So I think that’s a first step.

Of course I’m not going to tell you guys to go to panels and start scolding the ministers, but even among ourselves - us, our friends, our families, have that thought. If we want to talk about racism with the majority, first we have to do the work within ourselves.

A bit cliche but break the internalised racism that all of us had at some point. Once you’re able to understand that, you’re able to articulate that thought to your wider circles. That’s my suggestion.

Paul: So having these difficult conversations with other people but most importantly with yourself, being honest to your experiences and doing them justice by tackling these aspects of your history which you might have subdued over time, and thinking about “oh, wait a minute, that was actually pretty messed up, why did that happen to me?” That’s always a first step to being able to have these trickier conversations with other people.

For our last question, I’m going to ask one of Megan’s questions which I thought was a nice note to end on:

When putting the anthology together, how did the team try to strike or find the balance between hope & despondency that comes with the brown experience? So many of these experiences are experiences that are slightly more negative but how did you also balance that with a tone of—a note of hope, looking to something more optimistic?

Kristian: For us it was always important that when speaking about brownness, that we were not just talking about brown trauma, or brown negative experiences, but that we had stories of hope, of liberation in it and that was very important. When Mysara and I were first writing the performance lecture, Alfian Sa’at was our dramaturg and he kept asking “what are the moments of tenderness? What are the moments of solidarity that sometimes you can’t necessarily articulate but you just feel so viscerally?”

Those were the things that we also wanted to put into the book. And that’s why you have these stories of self-actualisation, of feeling powerful, of feeling like you have agency because that’s important, if not more important than the critiquing. The celebrating is what we try and convey.

Yan: Kris is exactly on the nose with that. This is a big part of what we wanted from the non-academic pieces as well; the academic pieces unfortunately veer towards a more difficult place, because that is the hard facts of it.

We were also looking for moments of community, joy, connection, whatever those could be, and how that can all flow together. We didn’t really want to make a book that people finish and go, “Oh, well. That’s too bad.” We wanted to make a book that can make people feel something, you know, just feel… there’s ups, there’s downs, that’s life.

Mysara: To add on, I’m going to read the last paragraph of one of my favourite pieces—when we did the open call for the under-18s—by Ashwin Rao, in front. For the three of us, we definitely need this in the book.

To sum up, there are good and bad things about being a minority. Sometimes I feel like I want to change my race, but then I think about my family and friends and decide I’m happy with who I am.

I love that.

Paul: Just to round us out, brownness is not just a reclamation of the term. When you think of ‘brown’ and how the older generations used to use the word ‘brown’, it’s usually in a way that’s derogatory e.g. “Eh you too brown already, don’t go out in the sun”. But by centring ‘brown’ in our usage of the concept, it’s reclaiming it as something that’s positive. For those who want to do further reading, there’s this term ‘negritude’ which does something similar.

It’s from black critical theory; taking the concept of blackness as something that used to be just seen as something negative, and by adding ‘-itude’ to it, it’s coming up with a new term, a neologism that describes blackness as a thing that is a quality of being rather than something that should be looked down upon. Brownness does something similar, but of course it’s something that would cause other people to go, “eh, importing from the West again.”

Thank you everyone for being here, and we look forward to hearing more from the rest of you on what you think from the book.

🤎

About the Speakers:

Kristian-Marc James Paul (he/him/his) is an activist and writer. He is a member of climate justice collective SG Climate Rally. Apart from his work in climate activism, Kristian also facilitates intergroup dialogues, partnering with organisations like AWARE to run community discussions on masculinity and male allyship. He was also a contributing author for white: behind mental health stigma (2020), an anthology on mental health in Singapore.

Mysara Aljaru (she/her) is a lens-based practitioner, writer and researcher. Mysara was previously a journalist and documentary producer and has also worked with various research institutions. An artist and writer herself, Mysara has showcased and performed at Objectifs, The Substation, ArtScience Museum and Singapore Art Week 2022.

Myle Yan Tay (he/him) is a writer, director, and actor. His works have appeared in PanelxPanel, New Naratif, and The Bangalore Review. He is an Associate Artist with Checkpoint Theatre.

Laika Jumabhoy has a background in Psychology and has worked the last four and a half years supporting survivors of domestic and sexual violence in Malaysia and Singapore, most recently as a senior case manager at AWARE. She is passionate about the use of expressive arts in trauma recovery and is the co-founder of So Let Us Talk, a peer led expressive arts support group that provides a safe space for survivors of sexual and domestic violence to come together and support each other. She is currently pursuing her Masters in Clinical Psychology and raising a little one.

--

About the moderator:

Paul M. Jerusalem (he/him) is a second-generation Filipino writer, creative, and researcher. Born in Singapore, his writing dwells on what it means to be in the spaces between. He is interested in issues of race, diaspora, transnational identity, gender, and sexuality. His writing has been published by Vagabond Press, Math Paper Press, and Ethos Books, and can be found in EXHALE: An Anthology of Queer Singapore Voices, Quarterly Literature Review Singapore, Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, and Rice Media, among others.